Ludus and Paidia

An occasional series of reflections on concepts from game studies, applied to board game design.

Let’s talk about play.

‘Play’ is a big word. We play a board game, sure, and we play a videogame. We play a game of tennis. An actor plays a role on stage. A chamber ensemble plays a sonata. Shakespeare played with words. I absent-mindedly play with the pen in my hand while talking on the phone.

We might use the word ‘play’ in all of these cases, but we’re talking about very different things in each case. We could make it simpler and focus only on games, setting aside all the other contexts in which we use the term ‘play.’ Still, playing a solo game of Gloomhaven, playing through a case in Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, playing Sushi Go! against your friends, and playing the lottery are more different than they are alike, even though we call them all ‘play’.

To really be able to think about what that activity means – about why it could be enjoyable and rewarding – we need a wider vocabulary than just ‘play.’

When it comes to design practice, what this means for us is that ‘play’ is too broad, too vague, too far-reaching to be very useful as a concept. When you’re designing a board game, you’re designing the parameters and the props for an activity that will occupy one or more people for a stretch of time, and that – if you do your job well – will be enjoyable and rewarding. To really be able to think about what that activity means – about why it could be enjoyable and rewarding – we need a wider vocabulary than just ‘play.’

Back in the 1950s, the French sociologist Roger Caillois already had the same thought. He tried to make sense of play by breaking it down into a whole taxonomy of different concepts – different kinds of play, if you will. We don’t need to get into all the details of this taxonomy here, but let’s take a look at his idea that all forms of play exist between two opposing poles: paidia and ludus.

When children first begin to play, Caillois says, there is no structure to what they’re doing. Their play is a kind of joyful excess of energy – running around with no apparent purpose, throwing things, taking on, dropping and reshaping roles in games of make-believe. This is paidia. With enough repetition, though, this free, anarchic kind of play starts to take on structure and form. Rules are established to regulate it. It becomes a focused attempt at facing up to a challenge by strictly regulated means. This is ludus.

It’s a bit more complicated than that, but, in a nutshell, we could say: paidia is about freedom, ludus is about rules.

Think of different ways you could run a D&D campaign. One group of players might be really into the stats, carefully optimizing their character builds, running a combat-heavy campaign to allow for plenty of number-crunching, and measuring out their movement using grids and rulers. Another group couldn’t care less about the numbers – they’re invested in their characters and the story they’re weaving, putting on silly or dramatic voices whenever their characters engage in conversation, animatedly jumping out of their chair to act out a scene. They might even ignore a roll or bend the rules if they get in the way of the story they’re playing out.

In this case, the first group is engaged in ludus, and the second group in paidia. In practice, most tabletop RPG groups will fall somewhere in between – you’ll immediately know where on the spectrum your preferences lie. And, of course, a game can be designed to be better suited to one kind of play or the other. A ludus player might gravitate towards a stat-heavy system like GURPS, while an almost entirely stat-less, improvisation-heavy system like Fiasco will better suit a paidia player.

Paidia is about freedom, ludus is about rules.

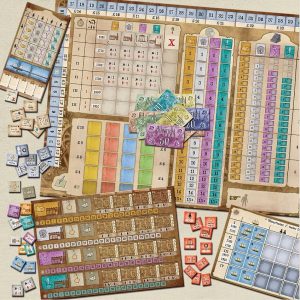

By and large, board games tend to swing very much towards the ludus side of things. This is true whether we’re talking about the complex, heavy systems of eurogames like Lisboa or The Gaia Project, or whether we’re talking about a strongly thematic, narrative-focused game like Arkham Horror: The Card Game. To play a board game is to engage with a system – it’s to read the rule book and understand what you should do, and then to set yourself against the challenge the game presents. All of that is pure ludus.

And yet, paidia still has a way of creeping in. I’ve yet to play King of Tokyo with a group that doesn’t eventually devolve into making monster movie roars and mashing the little monster cut-outs together whenever a successful attack is made. And when you’re playing City of Horror, you want to make the water tower blow up when your friend’s last two survivors are hiding out on top of it, even if that doesn’t get you any closer to your goal of surviving the zombie hordes until the end of the game. Even if their unique skills might have been exactly what you need next turn. It’s just fun to destroy things, and to see the horrified look on your friend’s face.

Every board game contains, to different degrees, the possibility for both ludus and paidia. Of course, different games will hew closer to one or to the other, and, for that reason, they will appeal to different players. Some will dismiss an almost purely paidic game like Funemployed as being trivial, frivolous or arbitrary. Others will be put off by the stone-faced rigidity of Arkwright.

As a designer, finding the balance between the two in a design is tricky. You want to design the rules and the structure that will give players a focused challenge against which to hone their skills. Yet, you also want to leave room for improvisation, for experimentation, for the joy of just playing around with no clear purpose or goal in mind. It’s something of a yinyang – the two kinds of play are almost direct opposites, pulling in different directions, and yet each contains the possibility of the other. Knowing which pole your game gravitates towards is a good step towards understanding the kind of fun you want your players to be having – and, as a result, which direction to push your design in.

Author: Daniel Vella

Daniel Vella lectures at the Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta, where he teaches courses on narrative in games, player experience and the formal properties of games. He studied literature before following a PhD at the Center for Computer Games Research at the IT University of Copenhagen. His research blends game studies, philosophy and literary theory, touching on a wide range of topics: from developing a theory of subjectivity in virtual game worlds, to examining aesthetics of the sublime and Romanticism in Dark Souls.