Excavation Earth: Dávid Turczi Designer Diary, Part 1

This week, we present the first part of renowned game designer Dávid Turczi’s two-part designer diary for Excavation Earth, Mighty Boards’ upcoming board game. The second part will be up next week, as we launch the Kickstarter campaign for the game.

Some games take form over a long weekend. Other games have a tiny, shining core that you just know is there, but that refuses to come to the light. You just don’t want to give up on it, even if it takes you weeks, then months, then years to dig it out. You may even find yourself putting that core into newer and newer games, until you find the one that sticks. That is when you really have to have the humility to take off your game designer hat, and nail the game developer hat to your forehead. Keep asking yourself every day: could this game somehow be better? This is the story of a developer hat nailed so deep into our collective foreheads that it no longer needs a child safety seat to travel. Or something. I think I confused my metaphors there.

This is the story of Excavation Earth – a game that definitely belongs in the second category. It is the story of how unicorns became aliens, and how a game ended up at a very different place from where it started out.

All quotes are mythical embellishments, by me. Don’t let history hold me accountable, I’m an unreliable narrator.

I think it was in the long-forgotten past of July 2016 that our story started. I was fresh off the high point of Mindclash’s Anachrony Kickstarter, and development was heavily under way on that. Dice Settlers was sitting somewhere on NSKN Games’ shelf waiting to be bubbled to the top, and I had just received permission from Vlaada Chvatil to design an expansion for Tash Kalar. Amidst this game-design charged atmosphere, my partner, Wai Yee, gave me a taste of my own medicine when I was shaken awake by her at 4 am during a warm London sunrise.

“I think I designed a game,” she says, sitting upright, with the lights on. “It has unicorns in it.”

“Cool. Write it down, we’ll build it tomorrow. Hopefully it’ll be good in a year or two, and then we can get it published. Good night.”

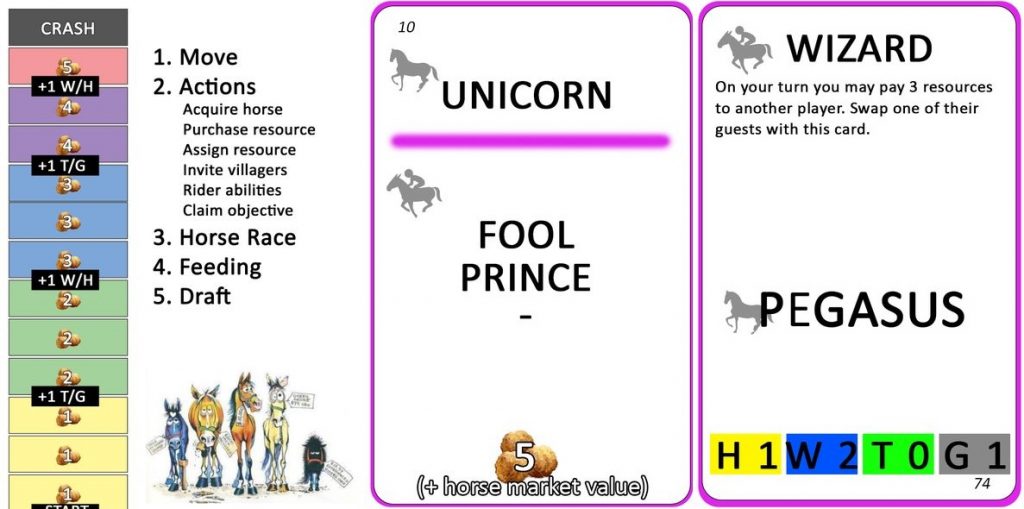

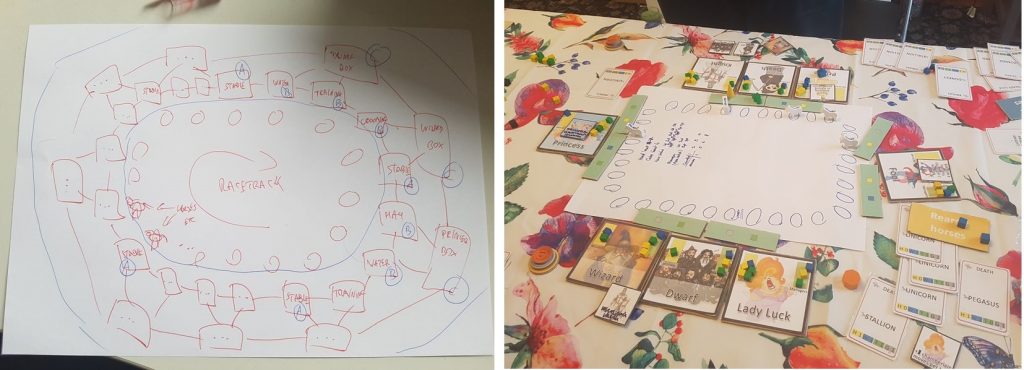

I turned around, trying to pull off the sleepy-grumpy act without sounding patronizing. But she didn’t relent. Next evening, a hand-stickered prototype with WordArt graphics awaited me at home. It had all the important members of the village: the dwarves, the princess-assassins, the fool’s guild, and the prince charming club on it.

“So, what do you do in this game?”

“You breed and train horses, and then you sell them to these weird people.”

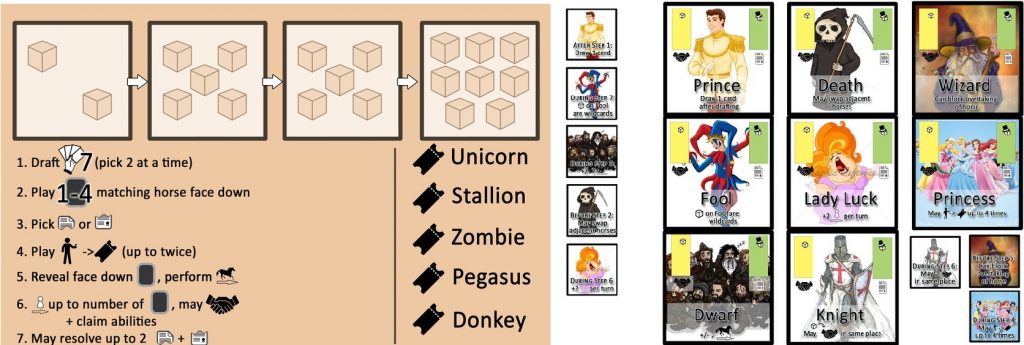

Over the next few weeks, we nailed down what mechanisms she wanted in the game. Multi-use cards came fast (Glory to Rome is everybody’s favourite back where I come from). Set collection was there all along. Horse-stock trading came later, when the straight “get these horses that your mission card says” game became boring. Card drafting came in when we had enough of people telling us “I didn’t draw any good cards,” no matter how many times we tried to explain to them that all cards are good. The four essential resources (hay, water, training, grooming) got stripped out eventually – as an unnecessary step distracting from card management – until we arrived at the game that all our friends knew as Wai Yee’s Unicorn Game.

Somewhere along the line, the horse trading turned into bet trading. You would buy a ticket and then try to sell it to the rich guys in the boxes the moment it seemed the horse was winning the race. In return, they got you business connections in town (shown as an area majority scoring for each guest). It made perfect mechanical sense. We essentially modelled “futures trading”, where you bought stuff at a fixed cost, sent out traders to buyers, and sold the goods when its projected futures value was at its highest.

My projected deadline of “This will be a good game in 2 years” was up, we liked the game, but, for some reason, nobody was “getting” it.

We spent the next months slowly improving both visualisation and terminology, one step at a time, in order to attempt to help our baffled playtesters. Some questions persisted: What am I doing here? Why are these horses going so slow? Am I trying to win the race for my horse? We explained that they are not your horses. Instead, you want the one to lead for which you hold the most tickets. The draft was smartly integrated so that some cards decided which horse moves forward (essentially bidding for price increases) while some were spent on performing your actions.

This is where Mighty Boards came in.

How did Wai Yee’s Unicorn Game slowly turn into Excavation Earth? Next week, the concluding installment of this designer diary will talk about why, and how,

Author: Daniel Vella

Daniel Vella lectures at the Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta, where he teaches courses on narrative in games, player experience and the formal properties of games. He studied literature before following a PhD at the Center for Computer Games Research at the IT University of Copenhagen. His research blends game studies, philosophy and literary theory, touching on a wide range of topics: from developing a theory of subjectivity in virtual game worlds, to examining aesthetics of the sublime and Romanticism in Dark Souls.