Excavation Earth: Dávid Turczi Designer Diary, Part 2

In the first part of this designer diary, Dávid Turczi talked about the origins of the game that would come to be Excavation Earth. That entry left off with the game having already undergone a great deal of development, but looking very different to what would turn out to be the end result – after all, it was still a game about unicorn racing, using meatballs as currency. How did the game go from there to alien treasure hunters digging up human garbage for their art galleries? This second, concluding part of the designer diary tells all!

While this was happening, Mighty Boards asked me for a game. We had just finished work on Nights of Fire, which we were all incredibly proud of (if you hadn’t heard of it before now, do yourself a favour and check it out, if for no other reason than it has my best solo mode ever), but it was ultimately “just” a wargame.

“Can we get a crunchy Turczi euro game with a quirky theme next?” they asked, coming off the success of Dave Chircop’s Petrichor with its quirky theme and interactive euro-goodness.

“Hey, do you want to check out this game I helped Wai Yee design?” I asked.

They looked, and they furrowed their eyebrows. “Can we get rid of the meatballs?”

First, their criticism was a market-driven one: why would anyone want a serious euro about unicorn racing? Second, Mighty Boards lead Gordon Calleja uttered the sentence that eventually led to him earning a credit on the box: “Yeah, but how does this make sense? How does the fiction of the game match its actions?”

The game looked like a race game, but the racetrack was just a visualisation of changing prices, so it confused everyone. And, of course, as mentioned, it was a weird thematic fit for their market anyway. “Can we try another theme?” Gordon asked.

Wai Yee and I sat down to compile three themes we could see as a better, natural fit for the “buy at flat price, manipulate future value, sell to markets, area majority to whom you sold to” flow of the game. Ultimately, a 1920s “Indiana Jones sells artefacts to a museum” theme won, and the game got a new title: The Great Excavationist. I briefly put my designer hat back on, and designed the meeple queue mechanism wherein visitors are represented by coloured meeples in the different museums (which later turned into buyers and bazaars), and the more meeples of one colour on the board, the higher the overall popularity of the artefact type.

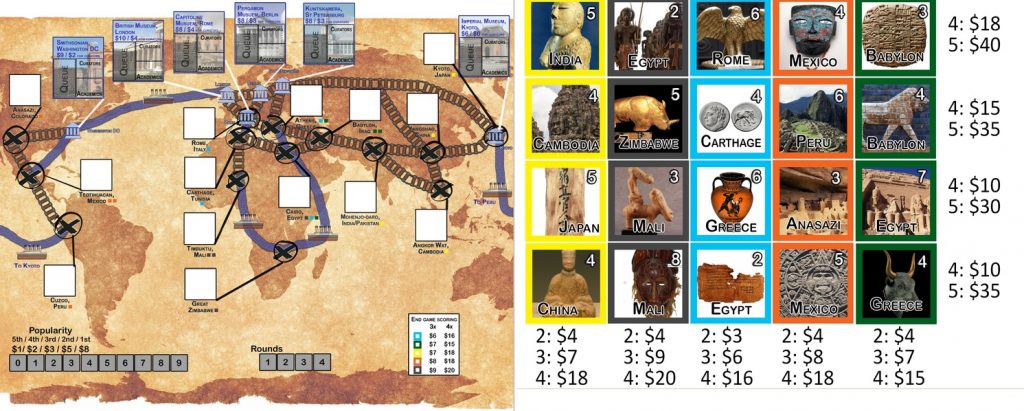

Around the same time, missions were removed from the game. Instead, we added a “bingo grid” that you are trying to complete as your natural evolving target for set collection. This evolved into the Gallery you see now in the final game. The area majority mechanics for museums were kept. For a while, so were the abilities for holding that majority. but eventually this was simplified into an end-of-each-round scoring. However, the original dual-use cards and the buying for an action and selling at “popularity value” were still there, while a black market was added as an alternative strategy to pursue.

The last fix was the turn structure. All the things that were steps in the turn structure of the unicorn game turned into actions of their own (move, survey, export, etc). The game turned into an “on your turn, take 2 actions, discarding a card for each,” a basic concept that was familiar to anyone who played Brass, which was our favourite game at the time and seemed such a natural fit. Since that day, I keep pitching the game to players as “a lighter Brass, but market manipulation instead of network building.” This is, of course, just a different way of saying “It is completely different, but this was the closest we came to any other game.” Plus, as I’d proudly point out, in Excavation Earth, each card has two different properties: its colour and its market. Totally different, you see.

The day came when we presented this new version of the game to Mighty Boards. I remember it was Dave Chircop who asked: “Can we add hot air balloons to make it cooler?” Gordon came up with a more radical idea – “What if we keep it the same as is, but with aliens?”

The title changed with the theme and Excavation Earth was born, but the game didn’t need much more changing beyond that. Asymmetric player powers were added to reflect the different alien factions you could play (some of them were returning powers from the Unicorn-VIP era). Then came another few months of gruelling work, with Gordon giving me a heart attack once every three weeks by suggesting we cut half an action out of the game altogether. I resisted one in three cuts, went along with many, but the questions he and the test crew were asking kept hammering the proverbial developer hat deeper into my head: can we make this better? From this line of thinking, some actions with four sub-choices got turned into two actions with different conditions instead, some limitations got removed, and a lot of things were renamed or represented differently to make more thematic sense.

I am proud to say the effort, the “Are you crazy?” Skype calls, and the endless reworks were all worth it. The final game carries all I saw in Wai Yee’s original unicorn game, all the mechanical finesse I managed to “eureka” into it in the “Great Excavationist-era”, yet every action makes thematic sense when Gordon teaches it, and is brought alive by Philipp Kruse’s magnificent art. Life leads all of us on strange journeys, and while Wai Yee and I are no longer together, I’m glad she trusted me to carry her passion project over the finish line. I’m confident that under Gordon’s guidance, we managed it. Now one question remains: how will you like it?

Author: Daniel Vella

Daniel Vella lectures at the Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta, where he teaches courses on narrative in games, player experience and the formal properties of games. He studied literature before following a PhD at the Center for Computer Games Research at the IT University of Copenhagen. His research blends game studies, philosophy and literary theory, touching on a wide range of topics: from developing a theory of subjectivity in virtual game worlds, to examining aesthetics of the sublime and Romanticism in Dark Souls.