Design Diary 3 – Writing Challenges

When I was approached to work on the writing and narrative design for Posthuman Saga, my interest was piqued, but I was hesitant.

In the other, parallel life I inhabit when I’m not working on Posthuman – the one lived out in university lecture halls and academic conferences – I study and teach narrative theory for digital games. In yet another parallel life – which, despite my best intentions, I haven’t revisited in a while – I had made some forays into fiction writing, and had grown to love the magic of conveying worlds through words.

So, when Gordon described his ideas for Posthuman Saga – that, in addition to combat encounters, this new Posthuman game would also feature a library of self-contained narrative encounters, each of which would give the player a gameplay challenge, a meaningful choice, and a little nugget of narrative payoff, and that these encounters would be stored in a physical storybook that players could leaf through – well, how could I not want to be a part of that?

And yet, I knew enough to know that designing, and writing, story for games is not simply a matter of tagging a couple of stat checks to the end of a chunk of text. Narrative in games brings up many challenges: the tug-of-war between player freedom and pre-scripted story, the exponential increase in resources required with every additional possible story branch, the difficulties in terms of perspective when the player is both protagonist and ‘reader’ of the story, and so on.

When it came down to it, I didn’t agree to work on the game in spite of these challenges, but because of them. They were challenges that set my mind racing.

In these diary entries, I’ll look at some of these challenges, and how tackling them structured my work on Posthuman Saga. For this first diary, the challenge I wanted to talk about is simply: brevity.

When I joined the project, I wrote out a sample encounter that, after a couple of drafts, I was really happy with. I set out a scene – an abandoned library that turns out to be not so abandoned – and worked to establish a palpable atmosphere of loss and melancholy. I created a character – an old librarian who had escaped from the horrors of the mutant apocalypse by retreating into a narrativization of her own life – and worked hard to find her a voice that felt right. And I made the encounter build towards a simple but meaningful choice for the player.

The feedback came in: “Great! Lovely sense of place, engaging character. You’re nailing the tone. But it’s far too long. Cut it down.”

So I redrafted, again, deleting carefully chosen but inessential adjectives, throwing out evocative details. I highlighted sentences I had painstakingly assembled over multiple drafts and hit Backspace. I pared my little story down to its bare bones.

In the end, I brought it down to about half its original length.

We read it out loud, testing how it would feel in the flow of the game.

It still felt far too long.

A few years ago, I was a part of the writing and editorial team of Schlock Magazine, an online genre fiction zine. At some point, we took what you might call a brave (or what you might also call a foolhardy) decision. Every day, for a year, we would publish a new piece of flash fiction. What this meant in practice was that, once a week, each of us would have to come up with a new story: a self-contained little crystal of narrative, a scene, an event, a character sketch, a mood, an atmosphere. And we had to do it in five hundred words or less.

Once you get down to it, that’s not that many words with which to tell a story. I would often find myself using up most of my stock of words just to set the scene. This is especially a problem given that I’m not usually one to use five words where I can get away with fifty.

I grew to understand that there were two reasons behind my prolixity. The first, bluntly, was insecurity. I would over-describe a scene because I didn’t trust that the details I had chosen were evocative or vivid enough. My stories would accumulate adjectives and adverbs, growing heavily encrusted with description, in the hope that some of it would stick.

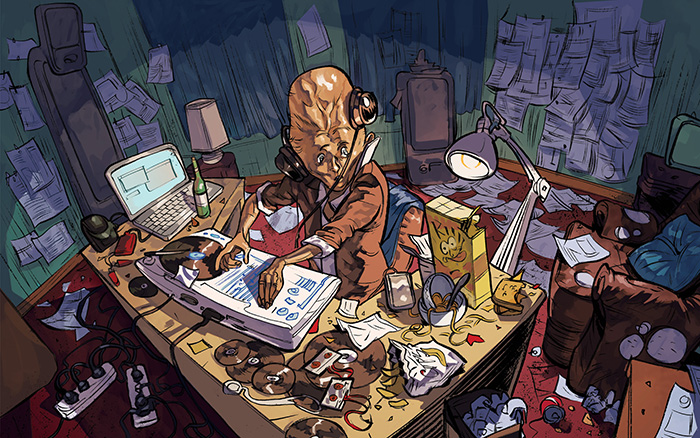

The second reason was the desire for total control. Each story would start off as a picture in my head: a landscape, a room, a face, and a quite distinct associated feeling. I wanted to make sure I communicated this picture, and this feeling, as precisely as I possibly could: I wanted to literally dictate the picture in the reader’s mind.

That’s not how writing works. When it comes to reading fiction, the imagination is a powerful thing – the reader is a co-creator, and a good writer knows his or her power only goes so far. The literary theorist Wolfgang Iser wrote about how the act of reading is a process of filling in the “gaps” between the lines, of moving from words to vision. The writer only has control over the words. The vision is all the reader’s doing.

Speaking of the nineteenth-century Pre-Raphaelite writer William Morris, and of his fantasy novel The Well at World’s End, C.S. Lewis wrote: “Can a man write a story to that title? Can he find a series of events following one another in time which will really catch and fix and bring home to us all that we grasp at on merely hearing the six words?” His point here is a simple one: the title of Morris’s novel alone is enough to bring to the reader’s mind an image of sublime mystery that any further elaboration can only diminish.

In the end, I managed to produce some stories I’m still quite happy with, but it was a difficult lesson to learn.

Once I started churning out a batch of encounters for Posthuman Saga, I wrote one in which the player-character comes face to face with a man called Dave, an incongruous figure in the post-apocalyptic landscape: a politician with the unnerving, over-polished shine of all politicians, running an election campaign as if nothing was wrong. I described his pearly-white teeth – in a world where toothpaste is not exactly readily available – the shimmer of his red silk tie, his pressed Italian suit, the spotless shine of his Oxford shoes.

But, again, this first draft was much too long. No group of board game players wants their play session interrupted for minutes on end while a laboured description is read out. The writing had to be punchy and to the point: I had no more than a sentence or two to set the scene.

Here, though, I had an advantage. Unlike the flash fiction I used to write, I didn’t need to create the world from scratch every time. The artwork on the cards, the terrain tiles, the character sheets, the box – all of that already communicates the colour and tone of this world, in which the fall of civilization has left the world we know in ruins and led things to be just a little bit weirder. Beyond this general scene-setting, the player’s engagement with the game builds an overarching narrative in this world: one of a desperate journey through dangerous terrain, with scarce resources and surprises around every corner.

Each narrative encounter in Posthuman Saga takes place in the context of this world, and this personal narrative. When players read an encounter out to each other, they have this shared frame of reference – so each encounter could cut right to the chase. And, of course, each encounter would also add a new detail to this world, and make it richer in the player’s minds for all future playthroughs.

In the end, I decided one detail would do for Dave. The shine of his pearly-white teeth (perhaps, in retrospect, inspired by a line in the Brikkuni song L-Eletti) glimmering in a world of mud and dirt and blood would be enough, on its own, to underline his ridiculous incongruity.

Next time, I’ll talk about another of the biggest challenges of writing for games: scripting branching narratives.

Author: Daniel Vella

Daniel Vella lectures at the Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta, where he teaches courses on narrative in games, player experience and the formal properties of games. He studied literature before following a PhD at the Center for Computer Games Research at the IT University of Copenhagen. His research blends game studies, philosophy and literary theory, touching on a wide range of topics: from developing a theory of subjectivity in virtual game worlds, to examining aesthetics of the sublime and Romanticism in Dark Souls.

I am excited!! Keep it coming! and I hope you have some stretch goals up your sleeves in case this thing blows up! 😀

Interesting, thanks for the insight.

I look forward to reading your work in the PH-saga story book.

I don’t think people really understand how good this game is going to turn out—I for one think it’s sounding incredibly strong thus far.