Design Diary 2 – Boardgame Narrative

The prominence of narrative in board games is increasing. We are seeing renewed efforts at fusing board games with narrative; not just in what are generally called “thematic” games, but also in euro games that have had a reputation of a stark division between mechanics and theme or story.

—Wooahh, not so fast there, Gordonius! You just flung three terms at your reader without explanation: theme, narrative and story. Are they the same thing?

Good point there, pedantic-me. This is something worth clarifying, because conversations around theme/story/setting employ a variety of terms, often interchangeably, which doesn’t help us understand which part of the cake we’re actually talking about.

—What cake?

Let’s start with story and narrative. Although these terms are generally used interchangeably they actually refer to different parts of the cake. Narrative has two elements to it: story, or the sequence of events that “actually” happened – and discourse, the structure and means of presenting the story. Story becomes narrative when it is structured and presented to the audience through some form or other (discourse). So, strictly speaking when we are talking about the specific instance of story we experience in a board game what we are talking about is its narrative. When we are talking about the overall events that happened in that world we are referring to story. Of course, in the case of a fictional world, the story is infinitely extendable and malleable and only becomes accessible once it is structured and communicated and thus becomes narrative. In summary: story is conceptual, while narrative is actual.

A related term is story-world. This is a concept coming from transmedia that describes the overall, accumulated history of a fictional world with individual narratives manifesting in a variety of media. This is an important concept in both table-top and digital games since they often depend on fictional worlds created as spaces to contextualize gameplay within them. While the distinction between narrative and story is helpful, at a conceptual level, to writers and designers, switching the terms story and narrative in everyday conversation is not going to create too much confusion since the concepts are intertwined.

Theme, on the other hand, is a problematic term. Theme, as it is used in board games, tends to refer to everything aside from the mechanics: the story-world, setting, narrative and pretty much anything that stimulates the imagination to understand the game as more than a series of abstract mechanics. While it’s a fine term to refer broadly to the “non-ruley stuff”, it’s not incredibly useful as a concept as it muddles too many different parts of a games’ fiction together. In other media such as film and literature theme refers to the central idea that a work attempts to put across and is organized around. For example, one of the central themes of The Road is love, another is survival. The setting of a work is the time and place (fictional or real) where that work is set. The Road is set in a post-apocalyptic near future, for example. What we often refer to as theme in board games is generally referred to as setting in other media.

In board games where the mechanics and the setting/theme are largely divorced theme might adequately cover the “non ruley-stuff” since there is little of it and it’s not central to the game. We can take the generic medieval setting of Dominion and exchange it for a planet inhabited by mushroom people that regard chocolate fountains as deities without it effecting the game in any way. As long as the mushroom people have some form of chocolatey currency, that is.

But when we use theme to refer to games with rich setting and a prominent narrative we are making it hard for ourselves to disentangle what we’re actually talking about. In these design diaries, I will therefore jettison the term “theme” altogether and use more robust terms such as setting, story-world and narrative.

—I still don’t see what any of this has to do with cake. Or stories! This was meant to be a fun article about those shiny things that make board games so… juicy. Like a nice Tiramisu drenched in Cognac…

Narrative is indeed a juicy part of board games. There is something magical about interaction with a set of rules turning into mental images of events in a shared world. Narrative has the power to both animate rules into rich shared fantasies and help us understand those rules in the first place. It gives an imaginative context to the problem-solving, cognitive challenges that good mechanics provide. It is thus no surprise that as board games mature and grow, both in the sophistication of their design and in the breadth of audience, narrative takes more of a prominent role in the hobby.

My interest in board game design has been infused with my fascination with narrative from the very first primitive table-top systems I designed as an 8 year old (at the insistence of a meticulous, systems-driven GM father). At 14 I started writing and soon after publishing poetry internationally. I then shifted to short story writing around the age of 18 and my focus on getting published grew enough that I set aside my table-top design. Eventually, I moved into designing and writing about video games starting at around 26 which led me full-circle back to table-top design, this time with a stronger focus on board games. After my first book on player involvement in video games I switched to researching narrative in digital games. As part of the process I decided to mock up a board game system that illustrate aspects of the model of game narrative I was working on. This game would later become Posthuman.

About two years down the line I was in a brainstorming session at a video game studio I set up with some friends called Mighty Box, and somebody suggested using the board game system I was working on as the basis for a digital board game. We decided to go with it but to also develop the board game first and release that on Kickstarter. The first Posthuman board game was meant to introduce the world of Posthuman and build a community around it while not giving much away about the actual lore of the world. We succeeded splendidly in this, giving away pretty much nothing of the lore! In retrospect, we should have been a bit more generous and less coy about the rich back-story and lore we had created for the Posthuman world.

Aside from not wanting to give too much away, another reason why there is so little exposition of the Posthuman story-world that we had labored for a solid year developing was my wanting to privilege what I call emergent narrative over scripted narrative.

The distinction between these two types of narrative is an important one to make, both in terms of board games and video games. This distinction was not one we needed to make when discussing narrative in film and literature since they are made up primarily of a scripted narrative – that is – one that has been designed, written and communicated by a creator or group of creators and interpreted by its audience. There is considerable variation in this process of interpretation, especially in more open ended or more metaphor-heavy works such as the movies of David Lynch or the stories of Jorge Luis Borges. But even in these cases, the creator has carefully designed the work to be interpreted. This is not the case with most games.

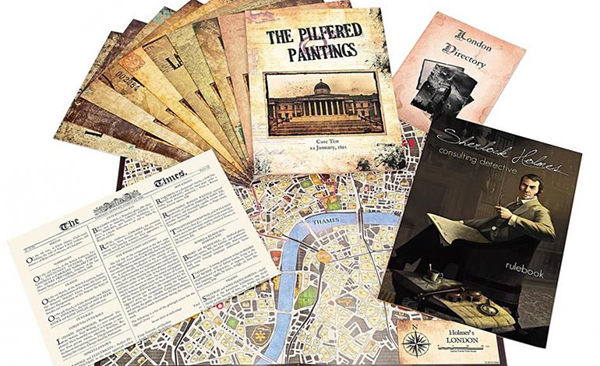

While games do feature scripted narrative, at times as a dominant part of the experience such as the pre-written stories found in Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective or Tales of the Arabian Nights, this form of narrative does not account for the whole narrative experience in games. Indeed, some might argue that this is the least interesting form of narrative experience, favouring instead the narrative that emerges from interactions with the game system and other players and takes place in the shared imaginations of the players. This is what I call emergent narrative.

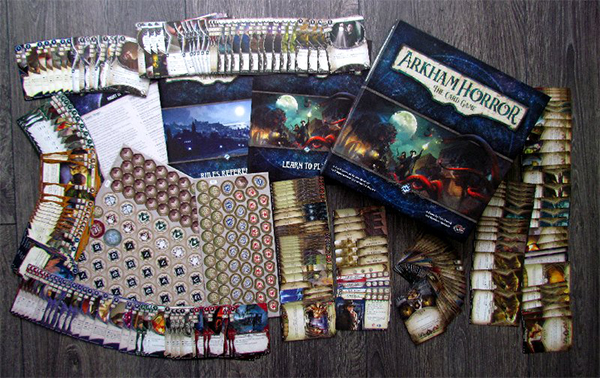

Scripted narrative covers all forms of narrative that is pre-written by the designer and/or writer and packaged into the games. Examples would be the introductory and concluding stories in Arkham Horror: The Card Game, the stories and directory entries in Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, the hero back-stories on the back of player boards in Vengeance and the chunks of text on Crossroad cards in Dead of Winter. It is also present in audio form in hybrid games such as Space Alert. Scripted narrative communicates the world the game is set in, the primary events that take place or have taken place therein and so on.

Scripted narrative forms can be differentiated by two parameters: the channels of delivery and the structure of the narrative. Channels of delivery are the different ways scripted narrative is conveyed to the player such as story-books, text on cards, app-driven voice narration, videos etc. The structure of a narrative varies more widely. Depending on the way the narrative is integrated into the mechanics, the chunks of scripted narrative can be revealed and linked together differently. The Arkham Horror card game, for example, has a chunk of scripted narrative at the start and another at the end, with the latter depending on an outcome dictated by the game’s mechanics. During the game players flip over two sets of cards (Act and Agenda cards) that have negative and positive scripted outcomes with accompanying mechanics to advance the scripted narrative of the game. Individual locations in the world also have short bits of descriptive text, as do certain enemies and allies. While these are not central to the unfolding plot of the scripted narrative, they add flavor to the story-world portrayed.

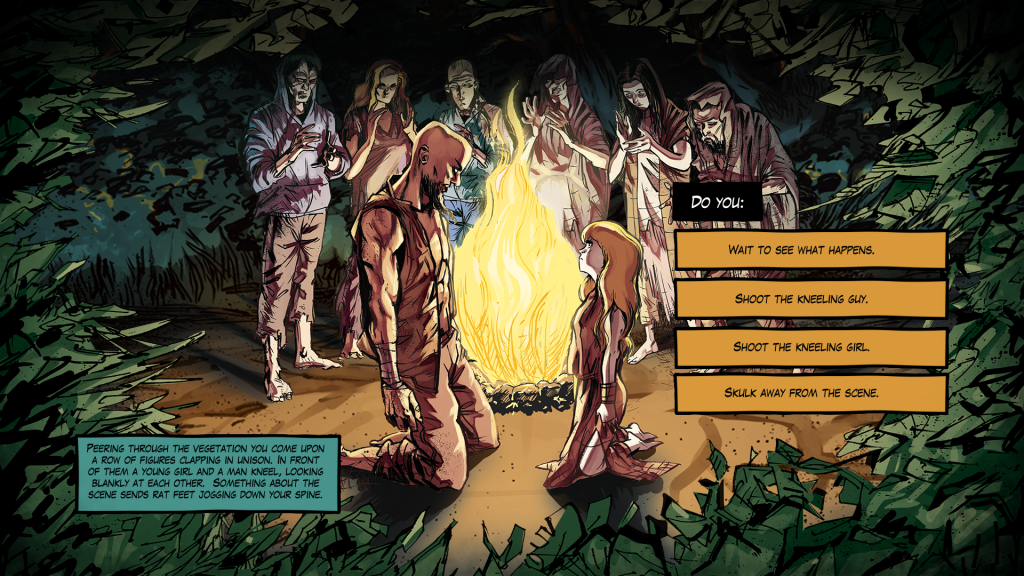

Emergent narrative is the more fascinating of the two, from a design perspective. This encompasses the story that is created in the player’s mind through interaction with the game’s mechanics, images, sounds, communication with other players and the scripted narrative. Emergent narrative can be viewed as a sequence of story-world events that come together in the player’s mind emerging from game-play actions. An example of this form of narrative would be a ship in the X-Wing game rolling 3 out of 3 hits in a shooting round and the enemy pulling off 3 evades on their respective roll as the two ships come head to head. Most (or at least some) players will not just see star and wiggly arrow icons on die-faces, but an X-Wing blasting away at a TIE Fighter and the TIE zig-zagging deftly, avoiding these shots. Designers can obviously provide more hooks for these mental images by weaving small scripted narrative elements that trigger in an emergent fashion through the game’s mechanics. X-Wing, for examples adds rules to stimulate this emergent narrative in the form of critical hit results on dice and scripted narrative chunks on the related critical hit cards. Critical hit results that are not absorbed by shields cause a special effect on the target. The cockpit might burst into flames or the hull cracks open, and so on. This is a mechanical outcome layered on top of the previous die-roll that creates an even more colourful set of images in the player’s mind. These emergent narrative elements, for want of a better term, can be viewed as a palette of oil paints that the designer hands to the players for them to paint their own internal images with.

The possibilities for this form of narrative in terms of design space are infinite. It is also the form of narrative that can create the most personal and meaningful forms of story when done right and when the players around the table are inclined to invest their imagination in the game. This is also the hardest form of narrative to design for since a designer can only create the architecture for it to be experienced, and not determine the exact content as is the case with scripted narrative. Another major challenge of designing for this form of narrative specifically is that a designer can only encourage their players to experience it, but not quite push them to do so, since these elements are dependent on the player’s imagination.

Identifying these two forms of narrative is crucial for furthering the conversation on game narrative, particularly in the case of board games. Scripted narrative and emergent narrative have an iterative relationship – one influences and is dependent on the other to work in the context of games.

This has gone rather longer than intended, so I’ll stop here for now. In a future design diary I’ll apply these concepts to the design of Posthuman and Posthuman Saga. Unfortunately this had to be a bit of a dry one, but without laying out some basic concepts out there to reference it’s hard to have a nuanced conversation about the complex and fascinating topic of narrative and games.

Till then!

-Gordon

Author: Gordon Calleja

Gordon Calleja splits his time between game design and academic game research. He designed Posthuman, a post-apocalyptic survival board game that was a big hit on Kickstarter in 2015, and was published in 2016. He recently designed and published Vengeance, a board game adaptation of revenge movies that was also a success on Kickstarter and has been published by Mighty Boards and co-published in German, French and English in 2018 by Asmodee and Greenbrier Games. He is currently working on a new board game in the Posthuman world called Posthuman Saga.

Gordon also designs video games and is the designer of the critically acclaimed Will Love Tear Us Apart, a video game adaptation of Joy Division’s track that was nominated for several international awards. He is currently also working on Posthuman:Sanctuary, a video game adaptation of the Posthuman board gametogether with the team at Mighty Box.

His research is multi-disciplinary in nature but features mainly on: game narrative game ontology and player experience, with a particular focus on immersion and presence in game environments. The latter is the subject of his book In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation, published by MIT Press. His current research and subject of his next book focuses on board game design and player experience.

Hi Gordon

Thank you for presenting your thoughts on a matter that I too have been thinking a little about.

I find it interesting (although not surprising) that many board games that are successful on Kickstarter are mainly using story to sell the game to the backers using the presentation video to deliver a scripted narrative rather than talk about the “ruley stuff”. The video tends to represents how the designer hopes the images will form in the players mind when they interact with the rules when playing the game. A good example of this might be your own Vengeance presentation video that tells a concrete Kill Bill’esque animated story with reference to the more abstract nature of how the board game actually plays as a system of rules.

Now, I don’t mind this approach as it may help inspire players to get the most from the game by helping the imagination along. I do however feel, that it is fairly problematic, that when creating board games where the emergent narrative is central to the quality of the game experience that so much responsibility is being put on the player. I know from my own board game group that most games we play are best if we invest ourselves in the game by role-playing our characters so to speak and tell out loud our own interpretation of what the rule interactions might mean in terms of the story. I find however, that most players are not well equipped for doing this.

You are right, that some games do a better job than others at enabling players in doing so, but if players are simply trying their best to win the game and take optimal decisions in relation to the rules then no sexy art direction or funny flavour text will achieve much because being the drunk reckless knight that always gets himself into trouble will not advance your chances of winning. Some games will simply have a character card with a rule that states that the drunk reckless knight character has a negative modifier of some sort to his attack or something of that nature. But if the player is not taking a drunk reckless approach to the game it will never transcend rolling dice and adding and subtracting some numbers.

This forms a game design paradox where on one hand we want the Sid Meier series of interesting choices in terms of game mechanics and we want players to be invested in the outcome of the game, but on the other hand we need players to suspend optimal behaviour in favour of making a great emergent narrative flourish.

How do you approach this problem?

Good question Jess. There’s a distinction between role-playing and emergent narrative. The former can be part of the latter but is not limited to it. Indeed, most board games that allow for emergent narrative don’t allow for much role-playing at all.

But your question seems to mainly prod at the tension between playing the game functionally – with an aim to win and thus number crunch versus playing the game to have those images in the mind. As you rightly point out, you cannot determine that experience for the player. That is something that a designer wanting to work with emergent narrative has to learn to live with. You can put as much hooks for the imagination as you want, but if the players are focusing on the functional aspect of the game then emergent narrative is not going to happen. Having said that there are ways of designing the same system with more affordance to create those sequences of images in the mind than others. Let’s take X-Wing for example. The fact that the results of the dice are “evade”, “hit”, “critical hit” and “focus” which are THEN further tied to cards or tables that yield further descriptive events one can imagine makes the game more likely to create emergent narrative than one where you roll a die, count up a number, deduct another number and figure out if the ship is destroyed or not.

And those two are not opposed design choices. What you want to do as a board game designer intent on having rules that generate mental images is to make sure that there is a mental image that goes with the rule you are creating. I say mental image not narrative here for precision’s sake – since some instances of mental imagery are not sequences of events and thus not a narrative per se. This means banging your head against the wall constantly to try and avoid having mechanics that are there just because they make the game better mechanically. That’s hard enough to do, weaving in story with that at as granular level as possible can sometimes be an impossible task – but one that a designer can strive for. I’ve smashed my head against the wall for months now on Posthuman Saga exactly because of this. While Posthuman privileged emergent narrative over mechanical tightness – that was the goal of that design – with Posthuman Saga I’m aiming for a lot more mechanical tightness and it’s been a hell of a challenge to both have clockwork, streamlined mechanics that also afford emergent narrative. When I did (mostly) manage to weave the two together (and man it was hard) without bulking up the rules, it was a hell of a lot of satisfaction. But yeah, a LOT of hard work and iteration to take it that extra step.