Excavation Earth: Imagining a world without us

Imagine a deserted Earth, long devoid of humans, visited by tribes of alien collectors eager to get their appendages all over the stuff we’ve left behind. This is the setting for Mighty Boards’ next game Excavation Earth, coming to Kickstarter next month. Though thoughts of an abandoned Earth have long been a part of our culture, they have become radically current in recent weeks. Startling images of abandoned city streets have us wondering again: what would the world look like in our absence?

The world without us

But first: is it even possible for humans to even imagine such a world? In his book In the Dust of this Planet, the philosopher Eugene Thacker argues that it is all but impossible for us to imagine the “world-without-us.” We are the centre of our understanding of the world, and we give the world a human shape. Imagining the world from a perspective that is not human is beyond the capacity of our inevitably human minds.

This doesn’t mean that the attempt hasn’t been made. Thacker’s phrase intentionally echoes the title of Alan Weisman’s remarkable bestseller The World Without Us, which sets out to give an exhaustive answer to the question, “What would the Earth look like if we were to disappear tomorrow?”

The chapter in which Weisman considers the afterlife of New York City is typical in both its exhaustively researched rigour and its almost poetic sense of the vast expanses of time and silence of a post-human world. Water flooding into subway tunnels would erode their supports, and the streets would cave in, bringing back the rivers that used to flow there. In two or three centuries, the rivets and bolts holding up the city’s suspension bridges would fail, and Manhattan would be an island again. The high-rises would start to fall, their destruction brought about by a hundred small disasters: joints would fail and rain would work its way in; seasonal changes in temperature would cause the water in pipes to expand and contract; vegetation would work its way into concrete. Millennia later, the glaciers of a new Ice Age would bury what little remains, leaving nothing more than “an unnatural concentration of a reddish metal” in the geological record to show that one of humanity’s greatest cities was ever there.

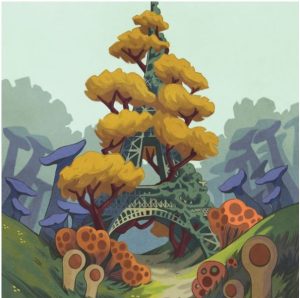

The 2019 board game Paris New Eden uses similar imagery of a formerly bustling metropolitan area returning to nature: in the game’s vivid illustrations, the French capital is overgrown with lush vegetation, as the frame of the Eiffel tower is wrapped in trees and Metro entrances are consumed by fungal growths.

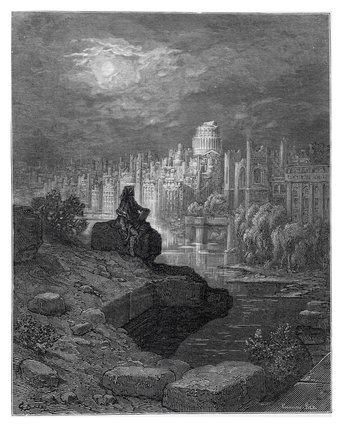

There’s a long imaginative tradition being invoked here. Hubert Robert’s painting Imaginary View of the Grande Galerie of the Louvre in Ruins was painted in 1796, when the museum was a mere three years old. In 1872, Gustave Doré produced his engraving The New Zealander, in which a wanderer looks upon the ruins of London – then the largest and richest city in the world, and seat of the most extensive empire the world had ever seen.

Meanwhile, over the past hundred years, the compulsion to imagine our present in ruins has become almost pathological. There’s no shortage of examples to mention, from Charlton Heston falling to his knees in front of the shattered figure of the Statue of Liberty in Planet of the Apes to the abandoned cityscapes of The Last of Us being reclaimed by the flora and fauna of the post-Anthropocene. And, of course, this brand of post-apocalyptic imagery is popular in board games as well, from Earth Reborn to our very own Posthuman and Posthuman Saga.

Looking out at the wasteland

Yet, the imagination of the fall of humanity is never total. In Robert’s painting, human figures wander the ruins. In Doré’s engraving, a lone wanderer observes the ruins from an elevated vantage-point. The clue to his identity is in the piece’s title. New Zealand, at that point, had been a colony –to the eyes of imperial Europeans, a civilized land – for less than three decades. It was the newest of the ‘new worlds’ of colonialism, so it’s not at all surprising that Doré would look to it to imagine a future civilization emerging from the collapse of the old world. And Paris New Eden, like many other post-apocalyptic board games, is also essentially about reconstruction: about a new beginning for humanity, rising phoenix-like from the ashes.

There is always, somehow, a human gaze enduring to look upon the downfall of humanity. Perhaps Thacker is right, and it’s all but impossible to imagine the world entirely without us. Just as we look upon the ruins of ancient Rome or Greece, so, some day, will the people of future millennia look upon the marks that our civilization left on the world – but, it seems, there will always be people left to look.

Yet there is also – far less frequently – a different trope: the traces of humanity being discovered and interpreted by non-human intelligences. The oft-misunderstood final scene of Steven Spielberg’s A.I.: Artificial Intelligence is one such example of this trope: in the ruins of a far-future New York City inundated by rising seas, advanced robots many generations removed from their vanished human makers attempt to piece together an understanding of their creators.

Excavation Earth takes a more tongue-in-cheek approach to this less-common trope. Its premise is a simple one: If there’s one thing our contemporary late capitalist society is good at, it’s producing mountains upon mountains of cheap, disposable garbage. What if, to some future pan-galactic society of art collectors and traders, exploring our planet long after we’re gone, that garbage is the most highly prized treasure in the universe?

Alien archaeology

Of course, archaeology is, to a significant degree, always about informed guesswork. In the remains of Başur Höyük – a 5,000-year-old burial mound in present-day Turkey – a set of 49 tiny, intricately carved stone figures, some representing pigs or dogs, some having simpler pyramid or egg shapes, are believed to be pieces of the earliest board game we know of. But that’s our best guess – they might have served some purpose we cannot even imagine.

The misreading of artefacts from a lost civilization is a familiar convention, even when it is human eyes doing the reading. In A Canticle for Leibowitz, Walter M. Miller’s classic novel of nuclear post-apocalypse, a monk travelling through the wasteland of what was once the southwestern US stumbles upon an unlooted fallout shelter. Inside, he finds a set of ‘relics’ he believes to have belonged to Saint Leibowitz, the mysterious founder of his order. One of these relics – a memo pad note with the mysterious text “Pound pastrami, can kraut, six bagels – bring home for Emma” – becomes the focus for centuries of theological interpretation, and grows to be revered as a holy text.

How much more drastically, then, would alien eyes misread human artefacts? With Excavation Earth, we wanted to give the sense of a non-human perspective trying to make sense of all the garbage of humanity. As they sift through our rubbish dumps and the ruins of our cities, how would they make sense of the sheer, incalculable volume of stuff we left behind? To begin with, the categories they would come up with to split objects up into groups would be the result of their own (mis)interpretation, and would be very different from the categories we use to think of our own stuff. Accordingly, ‘round things’ is one category of treasures to be found in the game, containing both footballs and tagines; ‘things which were alive’ is another, to which both hunting trophies and Godzilla figures belong.

Yet there is another, maybe even more jarring, source of incongruity in Excavation Earth’s non-human perspective on the human. This is probably most evident by way of comparison.

In the ruins of the Louvre that Robert’s painting shows us, one work of art remains intact. This is the statue known as Apollo Belvedere, a first-century Roman sculpture which Robert’s contemporaries would have been very likely to recognize. A few decades earlier, the influential German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann had singled out the statue as the pinnacle of the classical idea of beauty. Standing tall amidst the ruins, its implication is clear: art, and the eternal, classical standards of beauty it represents, will endure and survive.

Similarly, the board game Unearth presents us with the glorious ruins of an ancient civilization – towers, domes, colonnades and hanging gardens. It is the wonders of the past that endure, and that preserve “the glory of a bygone age.”

Things are different in Excavation Earth. The treasures these alien art lovers are competing for – a novelty license plate, a cheap souvenir snowglobe, a rusting hubcap, a rotting football – are hardly a testament to the glory of humanity. What they speak of is our insatiable consumption, our over-exploitation of the Earth’s resources, our poisoning of our own planet, our love affair with what is quick, easy and disposable.

Excavation Earth suggests that what will survive us is not our best, but our worst, our tackiest, our most ephemeral. Any future alien explorers will know us by our plastic junk.

On that basis, what will they think of us?

Author: Daniel Vella

Daniel Vella lectures at the Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta, where he teaches courses on narrative in games, player experience and the formal properties of games. He studied literature before following a PhD at the Center for Computer Games Research at the IT University of Copenhagen. His research blends game studies, philosophy and literary theory, touching on a wide range of topics: from developing a theory of subjectivity in virtual game worlds, to examining aesthetics of the sublime and Romanticism in Dark Souls.